In 2005, researchers from the University of Costa Rica became interested in the status of the jaguar populations in the country. In doing so, the need arose for obtaining more genetic information, since most of the existing data were morphological and ecological. This is how we started to get benefits from the field trips made by different groups of field researchers for collecting feces samples of wild individuals. Among such collaborators was the Jaguar Program of the Universidad Nacional, which studied jaguars in the Corcovado National Park and Guanacaste in particular. At the same time, we started working with other researchers from different parts of the country, and we also decided to study all individuals found in captivity in Costa Rica.

All carnivore species are highly vulnerable to the loss of their habitat, particularly the largest species, due to conflicts with humans, to their low population density and to their need for wide physical grounds to fulfill their basic needs for food, shelter and reproduction. Deforestation is the main problem for the conservation of mammals in Costa Rica, since it has caused the loss of habitats of these species.

It is known that the increase of fragmentation of the jaguar habitat represents one of the main challenges for future conservation efforts and for maintaining a healthy genetic structure for their populations. Due to their high vulnerability, active management plans are required, especially in countries where they are most endangered.

Population isolation has been linked to the loss of genetic variability and the increase of endogamy in several highly mobile species such as cougars, leopards, and, of course, jaguars. The genetic impact of population fragmentation and loss of connectivity may range from insignificant to severe.

By establishing the levels of genetic variability of feline populations and their population structure, the effects caused by habitat fragmentation and population reduction due to current threats may be determined. This is a preliminary step for establishing the best protection measures inside the conservation units, since this is a pioneering study for both Costa Rica and Central America. In order to guarantee long-term survival of felines in Costa Rica, it is essential to have conservation strategies that promote the maintenance of high gene-flow levels among the different geographic areas. Consequently, when carrying out genetic population studies, we will be able to determine biological barriers to their genetic flow and the degree of connectivity and isolation of the different populations in the country

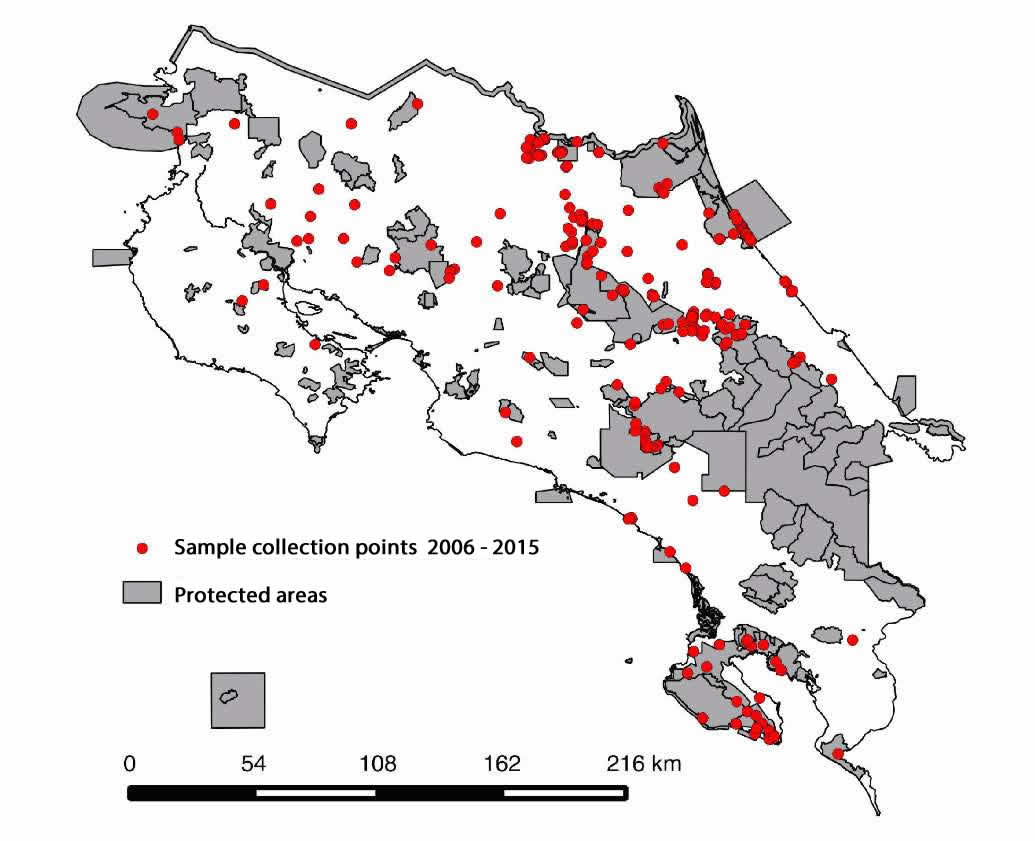

Our work begins in the field, together with researchers and organizations that study jaguars in their habitats, such as (ICOMVIS), the International Institute for Wildlife Management and Conservation of the Universidad Nacional - UNA. These collaborators collect samples of wild carnivores in different work areas; any material suitable for DNA extraction, such as feces, tissues, hair, bones and blood, is collected.

Samples are obtained from animals in captivity, rescue centers and exhibitions such as museums.

These samples arrive to the laboratory of Conservation Genetics of the School of Biology, where we proceed to extract the DNA. DNA is then sent to the Conservation Genetics Center and the Global Program of Feline Genetics of the Sackler Institute of Comparative Genomics at the Natural History Museum in New York, USA, for the remaining analyses.

The results provide us with information that allows verifying which feline species provided the sample, and we obtain an individual identity card with genetic information that identifies each individual jaguar. Upon analyzing the samples, we also obtain information about the direct movements of each individual. We can then study the populations as a group by means of their place of origin, which helps us to detect the behavior of the population, based on their gene flow, connectivity and isolation. Additionally, we can classify the jaguar populations using genetic variability indicators.

Of 672 analyzed samples, we have identified 65 jaguar samples, which allowed us to reach our minimum goal of 50 samples in order to have a significant representation to support the work conclusions. We have also identified other carnivore species in the collected samples.

According to the analyses of the samples obtained, we can observe that the genetic variability of jaguars in Costa Rica is moderate as compared to other populations of jaguar distributions. An additional 400 samples should be included in order to have more details about differentiation between jaguar populations in Costa Rica.

A strong genetic differentiation could represent a disadvantage for the population, given that such population would have little probability for long-term survival, either due to population isolation, to the onset of any disease or to climatic phenomena that may affect the immune levels of the species.

We at the Jaguar Foundation wish to express our deepest thanks to the contributors, who, like us, have believed in the importance of supporting the efforts of the state Universities in the conservation and preservation of the jaguar.